Reflections on February 2025 Reads

Fiction

Unquenchable Fire by Rachel Pollack

For the first quarter of this book I was really struggling to make sense of it. To put together all the rules of the world. To figure out the parallels to our own.

It did not go well.

But there was something compelling about the voice and the subject matter that didn’t let me put the book down. And once I stopped trying to find parallels in the culture presented and its idiosyncratic practices to those in our own world, I started to enjoy the book.

I came across the book after reading the essay The Querent in Alexander Chee’s How to Write an Autobiographical Novel. Chee mentions that the author, Rachel Pollack, is an expert in tarot, and while I know very little about tarot, it’s clear that the surreal and fantastical imagery throughout the book draws from this expertise.

There are probably depths in the layers of symbolism that I missed. There were frequent asides, excerpts from holy books referencing stories, some literal, some allegorical, some satirical, from a second revolution in the United States. A revolution that upended the march toward unending corporate busy work to some entirely different types of busy works steeped in magic and superstitions.

There were some clear parallels to our reality, particularly the visceral critiques of the expectations of women to be this and that but never those. And it’s not until the main character, Jennifer Mazdan, finally lets go of those expectations and her own expectations of others, that she’s finally freed to enjoy life from her own motivations, and not those of pressures from her mother, neighbors, her holy books, etc.

Which honestly felt like the lesson I needed to enjoy the book. To let go of my expectations of what a novel should be and of the expectations of what a novel and its author might have wanted from me. And to just read.

It was weird. But I liked it.

Vagabonds! by Eloghosa Osunde

This was maybe another book that required me to drop expectations and enjoy the ride, but in a slightly different way. I did this as an audiobook, and had very little context (aside from a passing recommendation from a very trusted source) so it took me a minute to realize that the booked lived somewhere between the realm of novel and short story collection.

There are common threads for each of the stories, specifically that they all take place in or in proximity to Lagos. All the characters are succumbing to the pull of Lagos, be it for work, for love, or for loss.

Osunde’s prose is lush with both captivating physical descriptions and subtle insights that made me shiver when I processed them. One of my favorite examples of this was a line from the reoccuring character Tatafo’s perspective:

“...hard walled as it is, there are cracks in power...and if there’s anything vagabonds know how to do, it’s to live in the cracks; to grow tall and thick as unfellable trees.”

I went into book knowing little about Nigeria and its histories and cultures, so there is probably more depth to the stories and characters presented that I missed. But Osude’s writing on the page alone is so rich that I got a ton from it even without that background.

One thing I did look up was the background of the recurring character Èkó. From what I could tell Èkó was a spirit, maybe a god, who pulled the strings of everyone and everything in Lagos like a puppet master. Though they were themselves beholden to the spiritual energies of the sea and the land surrounding Lagos. Èkó, I learned, is the Yuroba name for Lagos Island (this is where I go from Wikipedia to Google Maps rabbit holes...). And if I read right, Lagos Island was the original post-colonial capital of Nigeria. The seat of administrative power. The place from which to pull all the strings. So after learning this, Èkó’s character began to make more sense.

I’ve only scratched the surface here, haven’t even begun to discuss the in-depth characters, compelling and flawed, mysterious and lovely, that Osunde introduces and develops so intricately through the book. And the cast of voice actors did an amazing job conveying all of them. So I highly recommend both the book and the audiobook!

Essays and Insights

The Book of Delights by Ross Gay

I knew Ross Gay’s work was going to be on the syllabus for the creative non-fiction course I’m taking, so I decided to listen to one of his collections. I’m so happy I did. The concept for this collection (and its follow-up) was that he set a goal for himself to write about something delightful every day and then took those writings and transformed them into these insightful essays. His beautiful prose reflects his background in poetry and there are several essays that blur the line. What was most impressive was his ability to take a pleasant occurrence and turn it into an essay that actually spoke to difficult things, be they racism, poverty, violence, etc. There was a lot to enjoy, a lot to learn. It was delightful.

Femnist Theory: From Margins to Center by bell hooks

There are some audiobooks that I bookmark so much through the course of reading them, that I decide I need to buy a physical copy and transcribe my notes from it more methodically. This was definitely one of those books. I haven’t read many of the texts/scholars that hooks is in conversation with, but I felt this captured much of what always felt missing from mainstream talking points about feminism and interrelated social justice movements. One of my favorite sections was her discussion about the contrasts between feminism rooted in whiteness versus feminism focused on uprooting racist and capitalist systems that reinforce patriarchy. This was particularly illuminating for me because it hit on issues I could feel, but never knew how to articulate. I have a lot more to read on this and adjacent topics, but needless to say this book has become a foundational text for me that will likely influence my writings, fictions and otherwise, in some way shape or form from here on out.

Magical/Realism by Vanessa Angellica Villareal

This book was part memoir, part cultural/literary critique. I really appreciated Villareal’s astute observations about the publishing industry, its contradictions and legacies of racism. But also appreciated how these intertwined with her personal narratives. I think my favorite part of the book was her reading of the wall in Game of Thrones as an allegory for the Mexican/US border. She didn’t say this was at all Martin’s intent, but she was able to make interesting points by analyzing Jon Snow’s character. Snow, she felt, was the epitome of those who have lives on either side of the border. Who struggle with stubborn notions of loyalty to prescribed ways, versus the changing realities that he sees before him. I won’t dive into it further here, but it was a compelling reading and left me thinking.

Politics and Organizing

Tyranny of the Two Party System by Lisa Jane Disch

This book was recommended by a local organization raising awareness about the need for more parties to help build a more functional, more representative democracy. It was written in 2002, and (sadly) the issues raised in the book at still relevant, perhaps even more so now than they were then. The author, Lisa Disch, is a poli-sci professor and the work is probably geared more toward people who have some foundational academic background in the field. I don’t, but I still learned a ton, even though the significance of some sections were likely lost on me. At its core the book is less focused on the broad strokes organizing that is required to overcome our current duopoly and is instead focused on a specific barrier to it: the illegality of fusion. The book delves into a US of the past were third parties were quite common. One of the functions for making third parties viable was the ability for candidates to be endorsed by and listed on the ballot by multiple parties. When this was made illegal in all states (except New York), the ability for third parties to break into significance dissipated. Overall, an interesting and important read for understanding the history of our political duopoly in the US.

Emergent Strategy by Adrienne Marie Brown

This is another one of those books that I did in audio and will likely have to get a physical copy to go throw and take notes on because there were so many important learnings I want to think more deeply about. So, I don’t have too much to say about it now, other than that it felt like a really important and practical guide to organizing and doing so in ways that bring in quieted voices and leave out toxic practices that commonly make organizing less effective and sustainable. Will think more on this one and might have more to say after a reread, but I definitely recommend it!

What’s March Looking Like?

So far in March I’m continuing to slowly make my way through Envisioning Real Utopias which talks about the ways in which we might evolve beyond our current economic and political systems. (This seemed like a good chaser after having reread The Darker Nations and feeling hopelessness about the ability to build better systems.) I’ve also been exploring the work of Toni Cade Bambara after her name came up in several books over the last few months, so have read a few essays and am in the middle of The Salt Eaters. I also started Sofia Samatar’s The Practice, The Horizon and the Chain and am enjoying it so far. I’m also hoping to delve into some epic fantasy this year (a genre I usually shy away from) so I might try to pull one into my rotation this month and see how it goes. Hope to share more next month!

Art, Joy, and History

I walked into the Museum a bit nervously.

For blocks and blocks the sidewalk was lined with twelve-foot-high black metal fences. Modular ones. Temporary ones. Some pieces had doors, which were locked, but they were incomplete walls, you could step off the curb and walk right around them.

I walked into the Museum a bit nervously.

For blocks and blocks the sidewalk was lined with twelve-foot-high black metal fences. Modular ones. Temporary ones. Some pieces had doors, which were locked, but they were incomplete walls, you could step off the curb and walk right around them.

Somewhat more intimidating were the blocks lined completely with walls of porta-potties. J-walking was suddenly stamped out by toilets.

As I approached Museum from the North, the city feel of DC began to fade away. The beige federal buildings, which house offices for the NOAA, EPA, Department of Commerce, USAID and the US Customs and Border Patrol, eventually give way to the vast and open plaza of the National Mall.

On the left was the Museum of American History, a museum I’m sure I’ve never been to. Growing up in the DC area, I think I’ve been to almost every other museum on the mall, multiple times. Air and Space, Natural History, Sackler/Freer Galleries, The Hirshhorn, the National Galleries.

The only other museum on the mall I haven’t been to is the Museum I’m here to see today. The National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The Museum opened in 2016, while I was spending my brief decade on the West Coast. Brief because I should have been there at least a few years longer, but ended up leaving a few years shy of a decade. By the end of 2020 it was clear my life’s priorities changed, I had changed, the world had changed, so I had better change with it. Or change back.

So, I moved to the DC-area, back into my childhood home. Not quite into my childhood room, I set my daughter up there, and outfitted it way better than I ever had it. I moved into my sister’s old room (which, gets better sunlight... and has a bigger closet) and gradually began to figure out how to continue my life, work, single parent and become a care-taker to my parents. To somehow lean into role reversal and role expansion, while living in my childhood environment. I did my best. But I realize now, only a few years later, that I maybe possibly, needed taking care of in some way too.

Still, though, I have had a solid four years back in the area, with a cumulative of eight months spent unemployed due to layoffs, to check out more museums. Why I only managed to get to this a few days before starting work again, while the city was prepping for Trump’s second inauguration, was beyond me.

But I did make it.

The north side of the Museum was tightly fenced, forcing visitors to take a slightly longer more distant route around to the south side of the building to enter. I couldn’t tell if the fences were meant to protect the Museum and its grounds from inauguration crowds in a few days, or the other way around. As if the facts and ideas, the histories and truths, laying, waiting, inside, might unsettle the fragile realities of some in the crowds. I know it’s the first one, but...

There were no lines, so I walked in with a breeze (it was stupid cold, did I mention that?). I had my backpack, so as I approached the metal table with the security guards, I got that nervous apprehension, where you’ve not done anything wrong, but you think you’re suspected of it, so you end up acting suspicious. Maybe it was the high security inauguration setup that I walked through to get there, but I just walked in expecting the feeling of cold unwelcoming surveillance to continue.

The guard stopped me before I could take my bag off. “You’re good,” she said, waving me along with a warm smile, “enjoy the museum.”

It took me a moment to process this. Maybe my nerves needed a moment to melt in the heated air of museum. Maybe I just wasn’t expecting weight of misplaced suspicion to be lifted so easily. I thanked her and moved along.

The main floor of the museum was wide open. The ceilings were high and there was a gentle echo of middle school kids murmuring while their teachers and chaperones tried to herd them into one spot.

I squished my puffy coat into one of their free lockers.

Do all Smithsonian museums have free lockers? I’ve never used them if they do. I’ve definitely walked around other museums, uncomfortably warm, or fumbling with a coat or two in my hands. I suppose, it’s possible, even if there were lockers at those other museums, I might have never felt welcome to them. I don’t know if it was the security guard or better signage, but I felt welcome to the lockers here.

And then I made my way to the information desk to pick up a map. I was getting ready to flip through the booklet for the AfroFuturism exhibit (an exhibit that had sadly left the museum five months prior), when the elderly woman behind the desk approached me and pulled out a paper map and slid it on the counter.

She greeted me with a soft hello and a gentle smile. I don’t remember asking her or for a tour of the paper map, but I was happy to get it. To maybe, hopefully make it easier to parse through the 5-6 floors of exhibits I had about 2-3 hours to cover.

She pulled out a pen and circled the escalators to the left of us. She explained to me that the bottom three floors, the basement, the foundations of the building, housed the historical section of the Museum. Covering the transatlantic slave trade all the way through Obama, she said. She then flipped the page over and circled the top two floors, which covered present day (or at least the last ~100 years) of artistic, literary, musical, scientific, academic, athletic, military and religious aspects of African American cultures and histories.

I thought she was done, ready to send me off on my way after giving me the museum’s standard.

But then she flipped the page back over, smiled at me and leaned in as if she were delivering a secret. The concourse floors, she said, will take a while, hours. All the art, all the music, the fun stuff, she said, is upstairs. Her personal favorite being the Yoruba sculpture that inspired the exterior design of the Museum itself.

These floors downstairs, she said redrawing circles on the map, they’re no fun.

I thanked her and grabbed the map from the counter. But in that moment, all I really wanted to do was discard the map and everything she had just told me. To roam aimlessly into the depths of the museum for as long as I could.

According to this woman, the floors downstairs, covering five hundred years of history, were no fun. Were devoid of the arts. The arts were all upstairs. The implication being that the safe, feel-good aspects of African American culture were the ones worth engaging with. That the histories below deserved to remain buried, in the dark.

Before you ask, yes, she was.

She wasn’t wrong about one thing. To do the floors below, to really go through it, absorb the content, and appreciate curatorial decisions, the lighting, the placement, you would need hours. I only had three for the whole museum. I won’t go through all the exhibits here, there’s a lot to see, and if you’re ever in DC, it is probably the most important museum to see, to understand the history of this country.

What I did want to touch on was how wrong that woman’s implications of the downstairs floors were. Yes, they were difficult, morally and intellectually demanding exhibits. But at every section, there was also a history of people making art, expressing themselves and fighting to keep pieces of themselves in place or inventing themselves anew in spite of the horrors. The art was at times a statement of being, and at other times a pulse of rebellion.

I wished we had learned more about slave rebellion in school.

It’s possible we did and I just wasn’t a great student. I remember learning bits about the Haitian revolution. The name Nat Turner was somewhat familiar. Now that I’m thinking about it harder, we did watch Amistad in tenth grade. And Glory, if you can count that. Visits to Harpers Ferry in my early twenties told me a bit about the revolt led by John Brown. But the vast majority the history of slavery as taught to me in my memory was one of economic drivers for the empowered and the moral horrors they committed. Maybe I need to challenge myself and my memory on that more.

One thing I definitely don’t remember learning about was the 1739 Stono Rebellion in South Carolina. Here a group of people enslaved, some likely soldiers from the West African Kingdom of Kongo, led a revolt with ambitions to march to Spanish Florida which had promised freedom for fugitive slaves (source). Most of these people were killed in the revolt, formally executed or sold off. The revolt paved the way for the Negro Act of 1740, which only formalized the lack of rights enslaved Black people were to have in British America. No assembly, no growing their own food, no earning money. No learning to write, implicitly no education of any kind, except that which served the interests of white owners. The act also affirmed the rights white slave owners were to have over them, which essentially provided complete and utter obedience under penalty of death, without testimony, without appeal.

Example of a drum similar to one that may have been used during the Stono Rebellion.

I’m only reading about the Stono Rebellion, though, because this drum caught my eye. The inscription detail reads “Africans in the Lowcountry used drums for cultural practice, communication across distances, and even rebellion.” Which is why the Negro Act of 1740 banned the use of drums by enslaved peoples.

Specifically, article 36 of the law reads “...restrain the wanderings and meetings of Negroes and other slaves, at all times, and more especially on Saturday nights, Sundays, and other holidays, and their using and carrying wooden swords, and other mischievous and dangerous weapons, or using or keeping of drums, horns, or other loud instruments, which may call together or give sign or notice to one another of their wicked designs and purposes...” (source).

Musical instruments were listed beside dangerous weapons. Resistance to being enslaved was deemed wicked.

Article 36 from the Negro Act of 1740

Article 36 ends with a warning to slave owners: “...whatsoever master, owner or overseer shall permit or suffer his or their Negro or other slave or slaves, at any time hereafter, to beat drums, blow horns, or use any other loud instruments...shall forfeit ten pounds, current money, for every such offence...”

Just in case, the carelessness or sympathies of white slave owners and overseers were carefully checked. The delegated surveillance strictly enforced.

This reminds me briefly of Frederick Douglas’ appreciation for the poor white boys who, knowingly or not, committed great crimes to help Douglas practice his literacy as he walked to and from his errands on the streets of Baltimore. He credits their impropriety for some of the progress he made in those years.

The world that could have been, could still be, if empathy and connection weren’t criminal or taboo.

Statue of Phillis Wheatly

Less than two decades after the Stono Rebellion, a girl, likely less than ten, in West Africa would be sold into slavery and eventually be brought to Boston. She’d be bought by a wealthy tailor and merchant as a gift for his wife. These were the Wheatly’s, John and Susanna and they would name the young girl Phillis. The Wheatly’s were progressive, as progressive as slave owners come. They provided Phillis with an education, nurtured her literary talents and even ventured with her to London to advocate for her book to be published. And once it was published, they freed her (source).

There’s more to her story, more to her poetry, more for me to learn, but I’ll share this ending passage of her poem On Imagination:

But I reluctant leave the pleasing views,

Which Fancy dresses to delight the Muse;

Winter austere forbids me to aspire,

And northern tempests damp the rising fire;

They chill the tides of Fancy's flowing sea,

Cease then, my song, cease the unequal lay.

I wonder what world Phillis Wheatly was imagining. What things she wasn’t able to say. To pine for. What, despite her circumstances, despite being freed, did she have to pretend to be and think under the surveillance and violence of whiteness? What would happen if her poetry had been deemed ‘no fun’?

There were other artistic acts of music, song, clothing, dance, writing, oration embedded through these floors. A burl bowl with carvings harkening back to West African aesthetics. Music from Scott Joplin to Medgar Evans to Public Enemy.

Contemplation Court

The upper floors were wonderful and illuminating and I appreciate the buffer the curators gave between the two sections at the Contemplation Court. But I don’t think I would ever want to entirely separate the experiences. The pain and the horrors aren’t everything. We don't have to absorb the trauma of our ancestries in every piece of our art. Pain isn’t necessary to make art, to express oneself, to advocate for your own existence. But when art is made either because of or in spite of pain, I don’t think that means we should look away from the root of that pain. We can acknowledge the pain while we marvel and indulge in the vibrancy of the art and expression.

There are different kinds of censorship. I know to many people this woman’s words might have been innocent. But I wonder, how many people has she successfully dissuaded from seeing the history downstairs? From engaging with it? How many people went downstairs and decided she was right and hurried upstairs because it was too grim, no fun.

How often is our knowledge curated through a hazardous, well-meaning smile?

On Liminality and Collected Realities

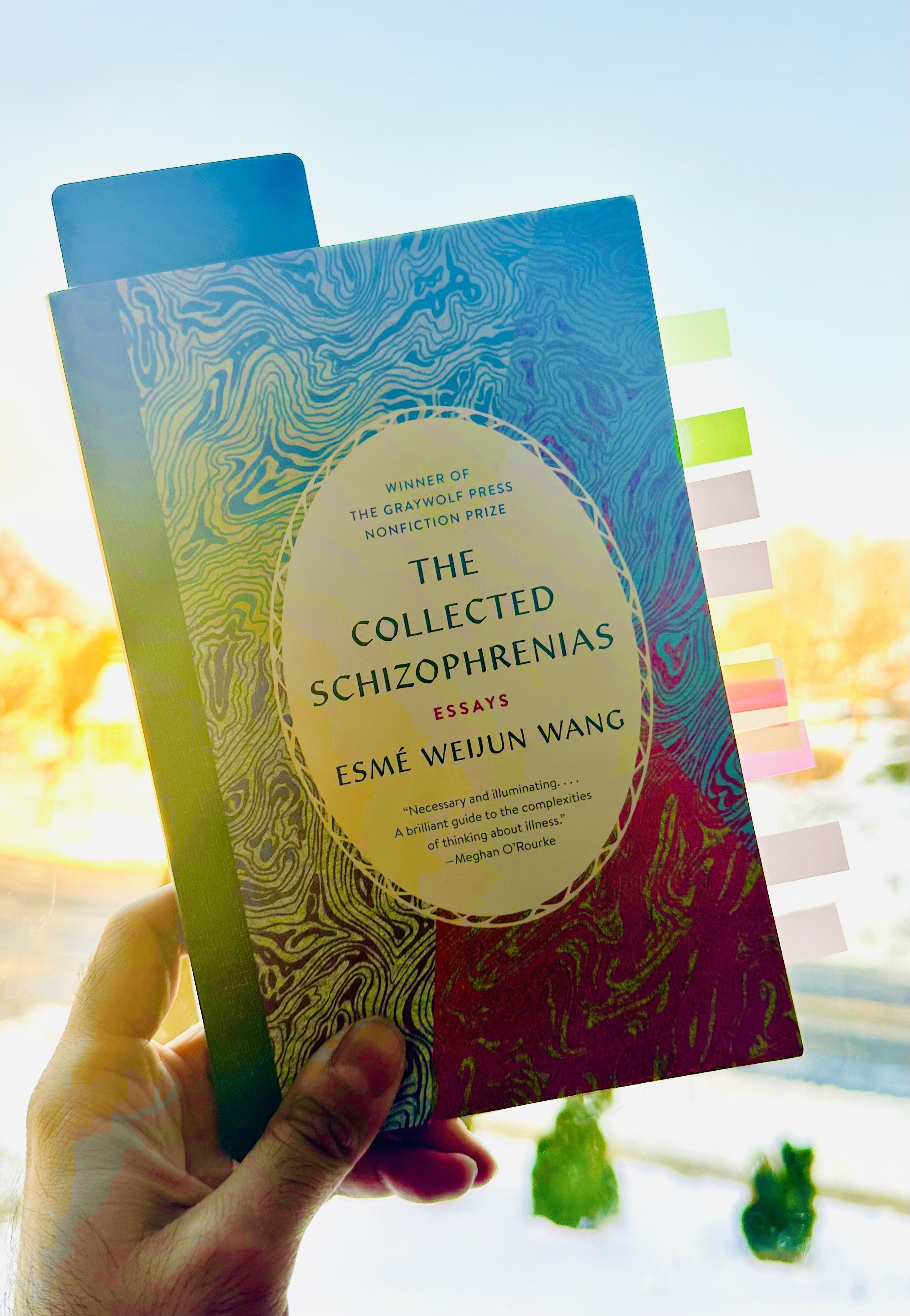

I picked up The Collected Schizophrenias mostly because the cover art and the title were enticing. I had no idea what it was about, beyond the title. This is a risky way to read books.

“During the worst episodes of psychosis, photography is a tool my sick self uses to believe in what exists. The photographs become tools for my well self to reexperience the loss...” [1]

I picked up The Collected Schizophrenias mostly because the cover art and the title were enticing. I had no idea what it was about, beyond the title. This is a risky way to read books. Sometimes it leads to starting and finishing a book that’s not right for me, at this moment, or ever. But other times it means falling into unexpectedly illuminating perspectives that push you down rabbit holes you’d never venture down, even if they were chalk full of things you needed to reexperience. Things you needed to unpack, to sort through, to discard or to reexamine.

“...They are a bridge, or a mizpah—a Hebrew noun referring to the emotional ties between people, and especially between people separated by distance or death-between one self and the other...” [1]

I haven’t seen schizophrenia up close, the way I have seen dementia and bipolar disorder. I’ve seen the way these other states of being warp realities and change people you knew well, you still know well, but now live elsewhere, even when they’re right in front of you.

How much control do we have over our realities? How much of them are objective and material, tied to hard points and constraints of the universe? How much of them are subjective and constructed inside our bodies? Assembled bit by bit, changing every day, to help us negotiate our survival with the material world we’re embedded in. A world where there are others who’ve constructed realities in which we are loved ones, in which we are negligible, in which we would be better off quieted, through abandonment, repression (or death).

“...The well person has the job of translating the images that the sick person has left behind as evidence.”[1]

If you’ve had a loved with a condition that causes realities to shift, drift, you know it’s difficult (impossible) to argue with them. To convince them something’s wrong with their perception of reality is a fruitless endeavor. And the irony of it is that you yourself are likely living in a fragilely constructed reality too. One that’s full of contradictions. One that abhors the brutality of capitalism, but contributes to it. One that abhors the injustices of colonial war mongering, but lives in the comfort of an imperial core, paying taxes and staying out of trouble.

How do you argue with someone who’s convinced that these same powers are coming for them? Are they wrong in the abstract, in the long term? Are they simply unwilling to accept your lack of urgency? Because time itself is different in these realities. The pacing, the sequencing, the causalities, all the craft choices we make as we tell the stories of the realities around us.

There are fixed hard points which all of us must concede to when confronted with them. Could I argue about the ways in which you construct reality when your home, your neighborhood, your child have been enveloped in curtains of white phosphorus? Could I tell you to listen to other perspectives, to reexamine your own, while the thick waxy air burns through layers of your skin, seeps into your blood stream, corrodes the inner walls of your heart?

That this substance is sometimes used to hide troop movements from infrared detection births more unrealities. The masking of a reality, a violent smoke screen.

Heat is an entire reality that for most of human history was beyond our sense of vision. It was something that was only real, only known, when we touched. But now it can be made real from great distances. Across rooms, across battlefields, across the Earth, across the solar system and beyond.

In 2023, a team of researchers working with the James Webb Telescope, estimated for the first time the average surface temperature of a rocky exoplanet. TRAPPIST-1b is a little bigger (+11%) than the Earth, and more massive (+37%). It’s also 99% closer to its star, TRAPPIST-1, than the Earth is to the Sun, and 96% closer to than Mercury to the Sun. Its orbital period is only 1.5 days, meaning its year is 99.5% shorter than the Earth’s. I don’t know why I’m telling you all this in percentages. I guess it’s just how I construct my own reality.

What I really came here to tell you is that at 41 light years away, the researchers were able to estimate its average starlit surface temperature is 230°C. Which means that life as we know it would be wildly unlikely. But I’d like to imagine what it might be like to live there anyways. I imagine, for no good reason, pockets of cooler shady spots on or inside the planet, pockets filled with the perfect mix of nitrogen and oxygen. Pockets where static electricity prickles my skin and fills the space with the subtle yet pungent odor of ozone.

I wonder, if your sky’s view was filled entirely by the surface of a star, would it still be a sky? TRAPPIST-1 is a little red dwarf star, only slightly larger than Jupiter, but much more massive, much more dense, a hard point explaining why it lives its reality as a star and Jupiter lives its as a planet. Our sky tends to be such a hard point, that it sometimes becomes mundane. A thing with different, yet consistent states. So the sky can quickly become a thing of unreality when something unfamiliar enters its view. A comet, an asteroid, a UFO, or the hugging presence red dwarf star.

I’ve gone off topic. I need a ribbon.

“When a certain type of detachment occurs, I retrieve my ribbon; I tie it around my ankle.”[2]

In “Beyond the Hedge,” Wang relays her experience consulting with a spiritual guide, a mystic of sorts, who recommends the use of a talismanic cord as a conduit, either to or from, liminal spaces. Wang ties a scented ribbon to her ankle as way to stay tethered to the material reality she shares with her partner, her friends, her family, to keep her from slipping away and getting lost into a reality that’s both here, but also somewhere else.

Liminality is one of those words or concepts that seems to have resurged in the zeitgeist in the past decade, or perhaps my awareness has become attuned to it, in search of spaces unburdened by the constructs I’ve built to negotiate my survival in this material reality.

One of my favorite genres of expressed liminality are Instagram accounts like @liminal.spacee that capture brightly colored, yet grainy, clean lined, abandoned places like shopping malls, water parks, office buildings. Abandoned might not even be the right word. It’s almost as if they’re places set up for a life that was never led. Set up for practice, an exploration of what life might be. A set.

There are also YouTube accounts, like nobody, that play ambient abstract music over similar images of quiet abandoned spaces. While this subgenre of music and imagery is enticing and subtly unsettling, it’s all also just a mishmash of 1980’s American nostalgia porn, isn’t it?

I’m curious, what is it about that 80s America that captures, for some of us, this feeling of liminality more so than the 70s or 90s? Are we looking for the spaces we occupied before we slipped into this meta-world of internet personas in the late 90s and into the 2000s? Are we searching for ourselves in the repressive cold war logics that we’ve continuously cozied back up to since 2001? I’m less curious about why we're trying to escape the present moment and more curious about why so many of us are trying to escape specifically to the 80s.

Maybe the algorithms just know what this aging millennial will find most comfortable. It’s tempting to call these platforms, these galleries of liminal spaces, liminal themselves. But they feel less like spaces and more like liminal funnels, built to trap and drain my latent energies, drip by drip, into the ever-expanding material oceans of other people’s wealth. An ocean that will lap at my shores, wearing me away, while I'm trapped, busied within the funnel.

“The line between insanity and mysticism is thin; the line between reality and unreality is thin. Liminality as a spiritual concept is all about the porousness of boundaries.”[2]

I read Piranesi a few years after the lock down, (I rarely make it to books while they’re on the surface of news cycles (in fact I might actively avoid them when they’re there...). I immediately understood why its release was so miraculously timed and I’m glad I waited until my own life had returned to closer to my expected reality. I was able to enjoy the dizzying yaw of Piranesi’s attempts to construct a reality, without falling into the despair of helplessly watching people close to me attempt to do the same.

If I remember right, Piranesi’s main talismanic cord was his own writings. His trail of breadcrumbs back to reality, like Wang’s photographs, were his journal pages, written snapshots of his former reality, lost in the cold marble galleries. Rediscovering them helped him rediscover who he was and how he ended up there. And while he could never be that same person again, it was an assurance that he was more than the lost entity lurking in a forgotten place. He could be someone else. There was more for him to become.

During the 2024 WorldCon panel Religion and Godhood in Science Fiction, a panelist (I can’t remember who, I wish I could) mentioned the work of the early 20th century mystic novelist Dion Fortune, as an occult ancestor to Piranesi. Something about this called to me and I ended up slotting her book The Sea Priestess in between my readings on the history of Sufism.

(I wanted to reread parts of the book for this post, but, perhaps appropriately, when I went to look for it, I couldn’t find the book anywhere. As if it slipped into my life, to briefly provide me access to its reality, and slipped away, leaving me only wisps of memories I’d constructed from spending time in priestess’ world.)

The book’s protagonist Wilfred, is utterly spiritually helpless. He’s privileged, cared for and arguably spoiled by his mother and his sister. Yet he’s constantly annoyed with their presence. He wants more from life, but has no idea how to get there until it’s drawn out by the mysterious entrance of Vivien Le Fay Morgan (a gentle nod to King Arthur and yet another rabbit hole of constructed realities to go down...). Wilfred’s talismanic cord, that Vivien ultimately has to coax out of him, is his ability to paint brilliant, realistic, emotionally charged epic scenes. A skill he knows he has, but doesn’t make use of until Vivien motivates him, helps him understand the transcendence painting provides, transporting him to scenes from past worlds, where he and Vivien play roles, important roles, of spirituality and sacrifice.

What are my own material or ritualistic hard points or talismanic cords, I wonder?

“I don't know that I have any,” I say to myself. “I don’t know that I need one. It may be best I stay away from liminal spaces, peeking through the porous boundary occasionally, but returning to the comfort of my own constructed reality and its material hard points.”

I say all this, but I write fictions.

[1](“L'Appel du Vide”, by Esmé Weijun Wang)

[2] (“Beyond the Hedge”, by Esmé Weijun Wang)

Reading Habits

Do you keep track of your reading?

I never used to. I’d read sporadically and aimlessly. A cover that caught my eye. A recommendation that nudged me at just the right time. A few times an author became an obsession and I’d read a bunch of their work.

Do you keep track of your reading?

I never used to. I’d read sporadically and aimlessly. A cover that caught my eye. A recommendation that nudged me at just the right time. A few times an author became an obsession and I’d read a bunch of their work.

But, in 2018 my writing aspirations took a more serious turn (that’s another post topic) and with that I realized I had a lot more to read. As I dove into the literary world and the science fiction world in particular, my TBR list grew and grew and at some point in 2019 I almost gave up on the whole aspiration because I felt like I’d never know enough, have read enough, to feel valid as a writer.

This was silly. There’s validity to writing where you are at any point in your life. Especially for yourself. It’s a process. If you want it to be. It can also be an aimless meander. I think I’ve found a nice balance between the two.

In January 2020 I decided I’d aim to read a book a week. This is probably a low standard for most of my reading/writing peers. But it was a steep aspiration for me, as someone who never read with regularity.

Reading was never a habit for me, never part of my routine. It was maybe more a random assortment of unexpected curiosity driven flings.

Tracking reading wasn’t a pandemic thing, but it certainly was a nice distraction during those chaotic months. Ultimately I hit my goal, closing out the year with 54 books.

And then I stopped.

2021 was a chaotic year: a cross country move, my dad’s dementia, a divorce and single parenting. Even when I had the time, I couldn’t get my eyes to stay on the page. And even when I did that, I couldn’t get the words to process. I didn’t stop reading entirely, but it was so slow that I stopped tracking and therefore have little idea what I read that year.

I was hard on myself for this initially, but gradually began to understand that my brain can’t read (or write) past the fog of trauma. There was a physical process to it that basically shut down during this period of my life.

But gradually audiobooks crept in. I could do audiobooks for non-fiction, but for fiction I deplored it, having trouble keeping details of character and place names straight in my head while following a long with the story.

It turned out this was a skill I could learn though. One I learned through How to Train Your Dragon…

At some point in August 2021, my kiddo and I ventured on a roadtrip to NYC and I decided to look for kids’ audiobooks. How to Train Your Dragon came recommended to we gave it a shot and made it through the first two or three books on that round-trip and finished all twelve books over the next few month’s drives to school. After that came Percy Jackson, Sayantani DasGupta’s Kiranmala books and more.

And after a year of listening to middle grade/young adult novels my brain kind of figured it out and I started listening to adult fiction as well.

Through this time I hadn’t given up on physical books entirely, but I would start more books than I would finish, often reading a few chapters never coming back.

It wasn’t until the second half of 2024, after I was laid off for the second time in 12 months, that I finally had a chance to take a step back and reflect on what had happened to my reading aspirations from 2020. So I made two resolutions: finish at least 52 books by the end of the 2024 and finish as many of those unfinished books as you can.

And so that’s what I’ve done. Ending the year with 62 completed books, 14 of them I had started prior to 2024 and never finished.

While it’s nice to track the numbers and check boxes for meeting goals, the real benefit for me in tracking this is so that I can go back and think about what I’ve read and how it connects back to my life and my writing. Maybe even revisiting ideas in these books and bringing them up for discussion in the future...